Two steps forward

The international goals to combat global warming, reached at a negotiation just outside Paris in late 2015, were adopted under the auspices of a treaty called the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Many people who are aware of the outlines of that treaty are unaware that it has a close cousin whose goal is to preserve the richness of the world’s plants, animals and other organisms. The two treaties both came into existence at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. And the biodiversity treaty is like the climate treaty in another way: the track record in carrying it out so far is one of failure. While the destruction of forests has slowed somewhat from its all-time highs, the loss of species seems to be accelerating, in part due to the overheating of the planet. Many scientists believe human activity has precipitated the sixth mass extinction in the Earth’s history.

The good news is that 2022 saw a major breakthrough in the effort to turn the Convention on Biological Diversity into a meaningful set of commitments. At a large meeting of the parties in Montréal, delegates who negotiated under the leadership of China agreed on a new framework embodying grand global goals meant to slow and ultimately stop the extinction of species and the loss of natural habitat, including the world’s remaining forests. This deal commits the signatories to bring 30 percent of the world’s land and 30 percent of its oceans into protected status by 2030. If carried out, this ‘30 by 30’ commitment would nearly double the amount of land held in protected reserves like national parks, and it would triple the area of the ocean covered as protected reserves.

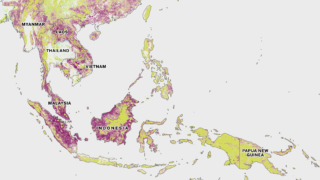

Figure 40: National commitments to land protection

The map shows each country’s commitment to protecting its lands, as a percentage of all land. These legal commitments are not always effectively enforced.

Source: The World Bank

Most of the world’s nations are signatories to the underlying treaty and endorsed the Montréal deal. The United States is the major holdout, having never ratified the treaty because of opposition among Republicans in the United States Senate. However, the United States helped to negotiate the deal in Montréal and encouraged other nations to sign it. President Joe Biden is pursuing a policy consistent with the treaty, attempting to preserve 30 percent of lands and oceans in the United States, though anything he puts in place by executive order is subject to reversal by a future president.

Just as with the climate treaty, the big question now is whether these goals can be achieved. Even some of the lands and waters currently under protected status are not truly protected, with governments often lacking the money or the political courage to enforce their own conservation laws. The biggest problems are in the world’s three main tropical forest basins: the Amazon, the Congo and Southeast Asia, including the islands of the Indonesian archipelago. By pulling the slider on the following maps, you can see how deforestation has proceeded in each basin over the past 20 years.

Figure 41: Forest loss in the Amazon

Data showing change in forest cover since 2000.

Source: Global Forest Watch

Figure 42: Forest loss in the Congo Basin

Data showing change in forest cover since 2000.

Source: Global Forest Watch

Figure 43: Forest loss in Southeast Asia

Data showing change in forest cover since 2000.

Source: Global Forest Watch

The motives for deforestation are generally simple: to convert the land into farms to supply commodities to overseas markets, or sometimes, to sell tropical hardwoods into those same markets. The governments of middle-income countries have often been left to their own devices in trying to enforce their forest-protection laws, even though the market pull was coming mainly from rich countries in the global North. Finally, however, this is beginning to change, which brings us to another big development from the past year.

After long and difficult negotiations, the European Union has finally agreed on a law to block the importation of products of deforestation into the 27 nations of the union. This is another major breakthrough, for it puts law enforcement in some of the world’s richest countries on the side of preserving forests. The EU has an arduous task ahead in setting up effective mechanisms to catch violators and enforce the policy, but at least the legal structure is now in place. A similar law has been introduced in the United States, with sponsors from both political parties, but it has not yet progressed in the American Congress. The United Kingdom is also considering stronger legislation to eliminate products of deforestation from supply chains.

Aside from these steps in consumer countries, we are also seeing serious efforts by forest countries to find a way to protect their natural resources consistent with their development objectives and with improving the livelihoods of their people. In Brazil, voters in late 2022 threw out the government of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right figure who had essentially declared open season on the Amazon, and reinstalled a past Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has a strong track record of fighting deforestation. Under his leadership, Brazil has already reduced deforestation to the lowest rate in six years. Lula, as he is universally known, also cultivated fellow heads of state to develop the Belém Declaration, a bold new vision and commitment for protecting the rainforest and supporting its people.1

Figure 44: Why forests are lost

Urbanisation, encompassed by the ‘other’ category, and commodity production are considered permanent drivers of deforestation. The other categories shown here are not considered permanent by Global Forest Watch.

Source: Global Forest Watch

Pressure for action is also being applied through climate commitments by investors and corporations. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero announced that transition plans that “don’t eliminate and reverse deforestation are incomplete,” and another organisation pushing corporate action, the Science Based Targets Initiative, has made clear that firms wanting its seal of approval will have to develop ambitious plans to eliminate forest destruction. An organisation called Global Canopy that tracks deforestation has expanded its efforts to hold corporations to account for their promises. Investment managers are also beginning to lean in, with the formation of the Financial Sector Deforestation Action Initiative, comprised of members with USD 9 trillion of financial assets under management; they have committed to tackling deforestation in their portfolios by 2025. Generation is a signatory to this initiative. Some consumer-goods companies, including Nestlé and Unilever, are reporting steady progress in cleaning up their supply chains.

Unfortunately, those positive developments from the past year were accompanied by bad news. The market for ‘carbon offsets,’ projects designed to limit forest destruction or otherwise keep carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, was thrown into turmoil over the past several years, culminating in declines last year in both the traded volume and the prices of certain types of offsets. These offsets are traded in a voluntary global market in which promoters undertake activities designed to halt or limit emissions, then create credits that can be sold to corporations or individuals who want to ‘cut’ their emissions without actually cutting them. This market, with many permutations, has grown to approximately USD 2 billion a year, relatively small in the scheme of things, but large enough to underpin some bold claims by corporations that buy the offsets.

Emissions claim made by Delta Air Lines

Delta is being sued by consumers who allege that its carbon-neutrality claim was fraudulent. The company denies any ill intent but is shifting its focus to other strategies for cutting emissions. Image: Montgomery Taylor

For example, if you happened to take a seat on Delta Air Lines, an American carrier based in Atlanta, within the last few years, you might well have had a napkin put on your tray table proclaiming Delta to be “carbon neutral since March 2020.” Of course, like every other airline, Delta was still burning jet fuel and emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. But it was also buying carbon offsets from projects like a Cambodian wildlife sanctuary and an Indonesian wetland. The marketers of the offsets asserted that carbon dioxide was being kept out of the air by their activities, allowing Delta to make the claim that it was offsetting 100 percent of its emissions.

Lawyers in California smelled blood, filing suit this spring on grounds of fraud, and seeking to have the suit certified as a class action on behalf of all Delta fliers. “Nearly all offsets issued by the voluntary carbon offset market overpromise and underdeliver on their total carbon impact due to endemic methodological errors and fraudulent accounting on behalf of offset vendors,” wrote the attorneys for the plaintiff, one Mayanna Berrin. Responding to the suit, Delta assured the public that it planned to stop relying on carbon offsets and would seek to cut its emissions directly. The company outlined a plan to run its fleet on sustainable aviation fuel made from climate-friendly biological feedstocks by 2050, with an interim target of 35 percent of its fuel coming from climate-friendly sources by 2035.

Whatever the merits of the lawsuit against Delta, it illustrates the magnitude of the controversy swirling around the market for carbon offsets.

It has been a Wild West of a marketplace, rife with conflicts of interest. The offsets are supposed to be certified by third-party verifiers, but they are paid for the certifications by project sponsors, giving them an obvious incentive to pump up the business. The promoters of carbon offsets range from deeply sincere environmental or indigenous organisations, trying to spend the money wisely, to fraud artists with criminal records. ‘Avoided emissions’ projects require constructing hypothetical scenarios that cannot always be verified: “Without our project, Forest X would have been cut down.” But would it really have been?

The recent controversy has led some potential corporate buyers to sharpen their pencils and look more closely at where their money is going. Companies like Microsoft,2 Stripe and others have gained a reputation for closely scrutinising any offsets they buy, and for being willing to pay extra for high-quality projects. Instead of ‘avoided emissions’ credits, many of these meticulous buyers have shifted their focus to ‘removal’ credits that draw carbon directly from the atmosphere. These include projects that restore native forests and others using new approaches like enhanced rock weathering on agricultural land, a technique that is capable of absorbing carbon dioxide from the air. Credible buyers have begun disclosing the prices, volumes and sources of all the credits they buy, an essential step to build trust in the market. The claims that these corporations make are also evolving to become less expansive and more accurate. Ultimately, we think governments will need to regulate this market if it is to contribute meaningfully to global climate goals; we need tough, legally binding standards governing how these projects are created and certified, as well as prohibitions on dubious marketing claims by the corporate buyers of offsets.

While governments are beginning to develop legally binding policies to protect biodiversity, they are making less headway in cutting the demand for meat and commodities that is the fundamental driver of deforestation. Global meat demand continues to rise sharply. Voluntary efforts to shift diets away from meat and toward plants have had modest success in some countries, but governments have been too afraid of consumer backlash to try policies — such as taxes on meat consumption — that might make a serious difference. Yet the mix of people’s diets has radical implications for greenhouse emissions.

Figure 45: Greenhouse implications of dietary choices

If you click to expand the chart above, you will see a breakdown of many common foods and the emissions incurred in producing them. Hovering over a bar provides additional detail. Beef is by far the most damaging food from an environmental perspective. People can contribute to solving the climate crisis by eating diets based largely or exclusively on plants.

Source: Our World in Data

In the face of rising food demand and the need to shrink the global footprint of agriculture, the only choice is agricultural intensification — producing greater yields on a given amount of farmland. This means bringing modern agricultural inputs like fertilisers to the small farmers, many of them women, who work modest plots of land across the developing world. Doing this in a way that does not worsen the environmental crisis is a major challenge. For instance, the production of nitrogen fertiliser, while essential to modern food production, has its own greenhouse footprint. Generation has invested in an alternative approach pioneered by Pivot Bio of Berkeley, California, in which the roots of cereal crops are inoculated with microbes that can pull nitrogen out of the air, cutting or eliminating the need to apply nitrogen fertiliser.

Figure 46: Investment in plant-based meat alternatives

Sales of plant-based meat alternatives have declined recently as consumers have come under pressure from high inflation. The chart shows that investors have lost some of their enthusiasm for the sector.

Source: Good Food Institute

Another way to cut the environmental footprint of food production is to substitute meat alternatives for meat. Unfortunately, companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat appear to have stalled at a relatively modest market penetration, perhaps because their products remain more expensive than meat itself. As the chart above shows, investors have been losing some of their enthusiasm for the plant-based meat alternatives as the difficulties these companies face have come into sharper focus. Still on the horizon are ‘cultured meats’ produced by growing actual meat cells in vats, though the environmental footprint and the consumer acceptance of these products — to say nothing of the cost — are still largely unknown.

- 1. Andreoni, Manuela and Bearak, Max. “Amazon Countries, Led by Brazil, Sign a Rainforest Pact.” The New York Times, 8 August 2023. Back to inline

- 2. Generation holds shares in Microsoft Corp., in its Global Equities Fund, and Microsoft is an investor in our new subsidiary, Just Climate. Back to inline